PCMG Workshop 7 February 2019

Millennium Knightsbridge Hotel, London

Conflict Management and Resolution

Sponsor: Parexel

This workshop comprised two related halves:

- Presentations of two outsourcing scenarios by experienced industry professionals, which highlighted different aspects of conflict and how they were addressed and resolved within the outsourcing arena

- An overview of coping with conflict, including various strategies and negotiation techniques that can be used to successfully manage the process, and in the process to achieve desired outcomes. This second section was delivered by a consultant experienced in the areas of making an impact, negotiation and conflict resolution

Governance managing conflict

Holger Liebig Senior Director, Partnerships, Parexel and Ian Wyglendowski, Head of Outsourcing, Contracts and Strategic Partnering, UCB

UCB is a multinational, mid-sized, biopharmaceutical company headquartered in Brussels and with products chiefly focussed on the areas of epilepsy, Parkinson’s, and Crohn’s diseases. In 2010 UCB decided to transform their outsourcing model from tactical to strategic, transitioning from a loosely coordinated suite of forty CROs down to two strategic partners – Parexel and PRA. Allocation of work is on the basis of full service and aligned with therapeutic strengths, with the exception of a small amount of specialist protocol writing

In 2014 UCB was experiencing conflict with their CRO partners, which was undermining the drive to increased value from their strategic outsourcing through development of true, trusting partnerships. An internal assessment concluded that UCB governance was too complicated with many different parties involved at different levels, a lack of clarity on roles, responsibilities, authority levels and KPIs, bound up in a punitive financial contractual framework which led to tension and mis-trust. There were escalation and performance issues, an adversarial attitude and unrealistic expectations with a focus on initiatives rather than delivery.

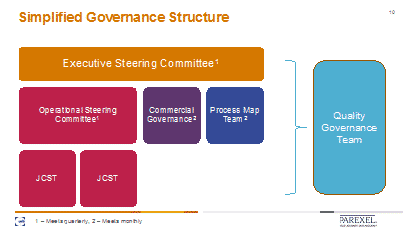

In response, UCB introduced changes in various aspects of governance and at all levels in the partnership, moving to a more simplified structure with fewer hierarchical levels, improved clarity on roles, responsibilities, communication and decision making, a focus on project delivery and risk management, increased focus on encouraging the right team behaviours, a stronger quality governance team with very senior involvement and they also initiated a commercial governance team to oversee the financial aspects of the relationship separate from the operational delivery. These steps helped to reinforce accountability on both sides throughout the partnership and encouraged study teams to resolve issues within their groups, rather than automatically escalating issues. Finally – and crucially – the governance management structure was distilled and simplified into just three levels:

- Study

- Function

- Partnership

The Executive Steering Committee, which represented the top of the governance hierarchy, comprised just three very senior individuals from each side, for example the Parexel CEO, reflecting the high level of shared commitment to improving the partnership

Then teams realised that divergent and dysfunctional cultures create ample space for deep conflict. Whereas partner-friendly cultures are inspired and encouraged by awareness, openness, flexibility, and consistency of purpose.

In 2015, building on the improved structure and process changes, Parexel and UCB asked staff involved in the partnership to comment on how they would improve things. To their shared surprise there was a lot of negative feedback, despite the changes implemented. Staff felt they had not been “taken on the journey”, the CRO were not identifying and addressing risks, there were too many metrics (n=43 KPIs), there was a lack of clarity over oversight, confusion over what was required for good quality and unclear expectations. As a result, Parexel looked at the UCB partnership in light of their experience of working with other strategic partners, identifying best practice and looked to see if there were opportunities for both sides to improve. Ultimately their shared goal was to build trust through clarity of processes and responsiveness, granting and taking ownership and encouraging an open and honest culture to resolve issues. Reporting was more focussed on relevant outcomes – providing clarity on expectations and clearly defined timelines.

Parexel introduced a policy of embedded partner liaisons – experienced senior-level CRO managers such as Holger being embedded within the sponsor company for 6-9 months, across global locations and with full access to UCB business and publicly supported by UCB senior management. In this way the CRO partner became an everyday colleague, working alongside their sponsor colleagues, able to identify issues at a very early stage, seeing the partnership from the perspective of the customer, and immediately available to address issues and misunderstandings and mis-conceptions before they impacted on the relationship.

Further work refined the oversight model into 26 key areas which were primarily concerned with tracking risks associated with study start up, execution and close out. These in turn provided the foundations for an oversight model for UCB clinical project managers acting at the project level and collaborating with their CRO counterparts. From a cultural perspective the UCB CPMs migrated to a new role – from delivering projects themselves to undertaking the oversight of CROs delivering projects. In addition, any member of the team at any level was empowered to give input on the partnership at any time. This was equitable, felt to encourage openness and was empowering to the staff. There were some clever IT-based tools such as the introduction of an interactive governance flow chart, which was designed with this holistic, team-based approach in mind. The Commercial Governance team was responsible for budgeting and processing of change in scopes, which freed up the project teams to focus on delivery and removed what had been one of the key sources of conflict. The outcomes included higher quality projects, reduced cycle times and less acrimony about relatively small amounts of money. Furthermore, a staff survey in 2016 provided ample evidence of success with 95% of respondents (Sponsor and CRO) strongly agreeing that the relationship was improved.

This presentation highlighted how a sponsor and a CRO in a strategic partnership had taken steps to work closer together, work smarter and to reduce the potential for conflict. A novel aspect was the model of embedding senior and experiences CRO staff within the client company to address immediate queries and concerns and to be the advocate of the Sponsor for the CRO. This was clearly an investment in the relationship by Parexel, who had the added benefit of greater clarity over the product and project pipeline for future opportunities to deepen the partnership. A second feature was the focus on organisational and cultural change to proactively reduce conflict and to resolve conflicts in a more consensual and supportive way when it arose.

Finally, it is apparent that CROs engaged in strategic partnerships are exposed to a wide variety of governance and oversight models (each sponsor is different) and are therefore well placed to advise on best practice models to avoid conflict.

Case study managing conflict through a CRO transition

Stacey Fergusson (Outsourcing Manager) and Jane Thomas (Clinical Project Manager) at Reckitt Benckiser (RB)

What happens when a pivotal clinical trial, representing the largest clinical investment in the Sponsor’s history, is undermined when a CRO partner files for voluntary bankruptcy during the clinical phase? This session considered just such a situation, which led to examples of conflict which are thankfully not common in the increasingly mature world of pharmaceutical development outsourcing. How did the Sponsor cope?

The pivotal study was a phase III efficacy and safety study and represented the largest study ever conducted by RB. The model was full service outsourcing, which included site contracting and meant the sponsor had no legal right for direct access to the clinical data generated by the sites. In addition, the CRO had sub-contracted the management of the project in one of the two territories to another CRO, which introduced greater complexity.

The CRO filed for voluntary insolvency between study set up and first subject first visit. This occurred without warning or notice period and followed the payment of early milestones by the Sponsor. In the turmoil that followed it was very difficult to get a full and complete picture of RB’s rights, as the sponsor, regarding critical aspects such as accessing the data and access to source data, payment to the investigators, payment to the sub-contracted CRO, indemnity provision for the sites and the clinical trial subjects and the regulatory implications. From a regulatory perspective, both the agencies and RB processed the CRO voluntary insolvency as a serious breach, with a strong emphasis on risk identification and mitigation to minimise the impact as far as possible.

Conflict in this case study arose not between Sponsor and CRO, but within the Sponsor between the clinical team and senior management, where there was a clamour for information that was not immediately available, a lack of consideration amongst non-clinical colleagues for the intricacies of compliance in this highly regulated area and the prospect of a costly and inconclusive investment. The situation was changing hourly in the early stages, the team were forced to deliver bad news to senior management and there was uncertainty around what to do for the best.

RB terminated the contract with the first CRO and introduced a rescue CRO. They then established a focussed, risk-based strategy for oversight, based upon four key aspects:

- Subject safety

- Data integrity

- Subject recruitment

- Budget status

In practice, the rescue CRO was appointed within 3 weeks, which remains the fastest vendor qualification and approval ever achieved within RB. A contract was agreed and signed with the administrator which protected the clinical trial data and granted access for RB and the new CRO. The investigators were eventually paid via an escro account administered directly by RB and the study was eventually delivered 10 months later than intended, but with recognition that it could have been a lot worse.

In conclusion the team felt there were lots of positive learnings that came out of the experience, such as the need for a robust financial assessment of the CRO at the start, for the sponsor to know how and when pass-through costs and site fees are being distributed and for clarity from the outset on ownership of clinical data The value of giving consistent messages around priorities and the excellent dynamics within the team, which meant they worked closely together during long hours with a strong, shared objective to deliver the study. In these ways the potential for internal conflict within the team was reduced.

One of the themes which consistently emerges during the various presentations of the PCMG Outsourcing Essentials training course has been the desire expressed by the delegates for more training in negotiation skills, particularly when agreeing budgets with CROs, either at the outset of a project or during the processing of scope changes. Negotiation styles are highly individual and changing your own negotiation style would require an investment in personalised training. However the organisers of this workshop were keen to include some tools and tips for effective negotiation in with the conflict theme as a key tool for resolving conflict.

The three P’s of conflict management

Martin Brooks, Accolade Consulting (Impactologist)

One of the themes which consistently emerges during the various presentations of the PCMG Outsourcing Essentials training course has been the desire expressed by delegates for more training in negotiation skills, particularly when agreeing budgets with CROs, either at the outset of a project or during the processing of scope changes. Negotiation styles are highly individual and changing your own negotiation style would require an investment in personalised training. However the organisers of this workshop were keen to include some tools and tips for effective negotiation in with the workshop theme as a key tool for resolving conflict.

Martin is a charismatic and energetic presenter and trainer with a central theme of creating an IMPACT, whether that be in negotiations or in marketing to create an impact. His first observation was that conflict occurs all the time and at many levels and sometimes conflict is good, but other times it can be corrosive and undermine relationships. The key is to learn how to manage conflict to achieve your desired goals.

Martin explained the three P’s model of conflict management:

Three P’s of conflict management:

- Prevention

- Perspective (deal with it)

- Persuasion

- Prevention: Assess risk, identify worst case scenario and plan for it. “Plan for the worst, hope for the best”. Avoid conflict through prevention.

Delegate suggestions to avoid conflict:

- Understanding other parties motivations (“walk a mile in someone else’s shoes”)

- Communication – clear and open

- Consistent and common goals

- Transparency

- Trigger points – know about other party’s hot button

Martin’s prevention measures:

- Use SMART goals to define delivery and avoid misunderstandings

- Clear, measurable variables (time, quality etc)

- Clear milestones agreed

- Communication channels for feedback (who, when, how?)

- Active information-seeking by BOTH parties

- Proactive encouragement of communication

Delegates were strongly urged not to enter conflict negotiations with a raft of assumptions about the other party’s position:

- “Common sense is not so common” Voltaire

- “Assume makes an ass out of u and me” Anon

- “Assumptions – the enemy of clarity and the enabler of conflict”

He gave an example of the baggage handling disruption when Heathrow Terminal 5 was first opened. The assumption in the popular press (and potentially with the senior management) was that the staff were striking for better pay and conditions. However, the reality was the staff car park had not been opened early enough and they were all late through no fault of their own!

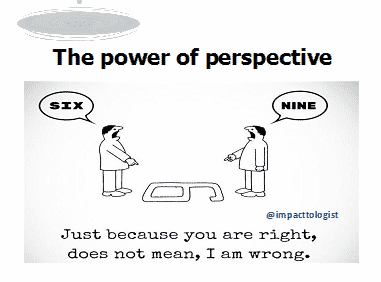

- Perspective

Martin introduced the simple exercise of drawing the number “6” on a piece of paper to demonstrate the ease with which people on opposite sides can have different perspectives.

Neither party was wrong, but we often present our perspective as right, which means any other perspective is wrong and represents a potential conflict. In this case the effective negotiator would bring evidence to support their perspective whilst accepting that their opponent might bring evidence to support their perspective.

Quality of evidence should be the deciding factor, but, if not irrefutable, then this can lead to conflict. In case of conflict you can invoke the power of reciprocation (you have a right to your view and I have a right to mine).

3. Perception

Martin outlined two common tactics for imposing your perception:

- Three-step assertive technique:

- Acknowledge the other persons view “I understand from your perspective….”

- Fully acknowledge their perspective

- Give your perspective “However based on all the evidence, I believe……”

- Preferred way forward “Therefore I suggest…”

- Repeat as necessary (broken record technique)

- If all else fails then Insist as a last resort to impose your perception to avoid descent into conflict.

- Constructive feedback model

- Ask for permission (even if you don’t need to)

- State what you are not getting

- Express the implications of that – why is it a problem?

- State what you’d like to see instead

- Ask for their ideas on HOW (not if) they are going to do it

- Agree next steps (SMART)

Negotiation tools:

Tradeables are a common tool used in negotiations. Tradeables are things that you are prepared to give away to “sweeten the deal” in other words to break down the resistance of your opponent. The best tradeables are things which you control, they have little or no value to you, but represent a lot of value to your opponent. Martin gave a personal example of his accepting a very low pay for leading some training at the London Business School. The tradeable was prestige – high value for him in having LBS training on his CV and LBS amongst his clients. But no cost to LBS, who were able to use their prestige as the tradeable to get him to accept a low rate for the work.

Tradeables:

- I know what I want but what am I prepared to give away? Give as much thought beforehand to what you’re prepared to give to get what you want

- What have you got that is of value to them?

- Equitable trading. Think of the value to them NOT the cost to you

- Best tradeables have little or no cost but high value to your opponent

- Reputation, contacts, credibility. Excellent examples of tradeables

Symmetry technique:

- Make any offer conditional (“…as long as….”)

- Always make a concession conditional. Don’t give concessions away

Packaging:

Packaging is when you sell unpopular items in with attractive and desired items as a package. A successful example of bundling is the packaging of green, yellow and red peppers together in the grocery store. People buy for the red pepper and the lure of the bulk purchase, but the total price is more than the constituent parts.

This was an entertaining, engaging, participative and informative session that was enjoyed by all the delegates and which cemented some key negotiation techniques in a very short time.

Do you have any examples of conflict between Sponsor and CRO and how these were successfully resolved? If so we would be pleased to hear from you for anonymised case studies which will help to establish best practices for the outsourcing community. Drop us a line and share your conflict examples at admin@pcmg.org.uk

David Davies